Why Simone Giertz, the Queen of Useless Robots, Got Serious

Simone Giertz came to fame in the 2010s by becoming the self-proclaimed “queen of shitty robots.” On YouTube she demonstrated a hilarious series of self-built mechanized devices that worked perfectly for ridiculous applications, such as a headboard-mounted alarm clock with a rubber hand to slap the user awake.

This article is part of our special report, “Reinventing Invention: Stories from Innovation’s Edge.”

But Giertz has parlayed her Internet renown into Yetch, a design company that makes commercial consumer products. (The company name comes from how Giertz’s Swedish name is properly pronounced.) Her first release, a daily habit-tracking calendar, was picked up by prestigious outlets such as the Museum of Modern Art design store in New York City. She has continued to make commercial products since, as well as one-off strange inventions for her online audience.

Where did the motivation for your useless robots come from?

Simone Giertz: I just thought that robots that failed were really funny. It was also a way for me to get out of creating from a place of performance anxiety and perfection. Because if you set out to do something that fails, that gives you a lot of creative freedom.

You built up a big online following. A lot of people would be happy with that level of success. But you moved into inventing commercial products. Why?

Giertz: I like torturing myself, I guess! I’d been creating things for YouTube and for social media for a long time. I wanted to try something new and also find longevity in my career. I’m not super motivated to constantly try to get people to give me attention. That doesn’t feel like a very good value to strive for. So I was like, “Okay, what do I want to do for the rest of my career?” And developing products is something that I’ve always been really, really interested in. And yeah, it is tough, but I’m so happy to be doing it. I’m enjoying it thoroughly, as much as there’s a lot of face-palm moments.

Giertz’s every day goal calendar was picked up by the Museum of Modern Art’s design store. Yetch

Giertz’s every day goal calendar was picked up by the Museum of Modern Art’s design store. Yetch

What role does failure play in your invention process?

Giertz: I think it’s inevitable. Before, obviously, I wanted something that failed in the most unexpected or fun way possible. And now when I’m developing products, it’s still a part of it. You make so many different versions of something and each one fails because of something. But then, hopefully, what happens is that you get smaller and smaller failures. Product development feels like you’re going in circles, but you’re actually going in a spiral because the circles are taking you somewhere.

What advice do you have for aspiring inventors?

Giertz: Make things that you want. A lot of people make things that they think that other people want, but the main target audience, at least for myself, is me. I trust that if I find something interesting, there are probably other people who do too. And then just find good people to work with and collaborate with. There is no such thing as the lonely genius, I think. I’ve worked with a lot of different people and some people made me really nervous and anxious. And some people, it just went easy and we had a great time. You’re just like, “Oh, what if we do this? What if we do this?” Find those people.

This article appears in the November 2024 print issue as “The Queen of Useless Robots.”

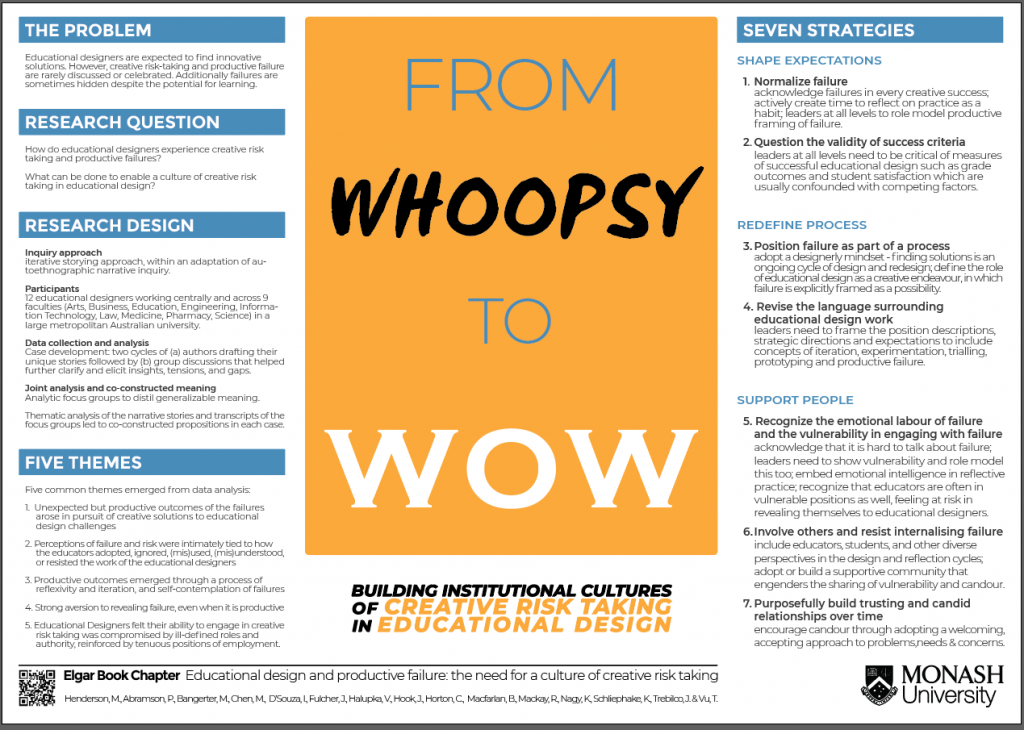

This chapter focuses on the creative risk taking involved in educational design and is an exciting collaboration between DER member Prof Michael Henderson and 12 senior Educational Designers embedded centrally and within 9 Faculties.

This chapter focuses on the creative risk taking involved in educational design and is an exciting collaboration between DER member Prof Michael Henderson and 12 senior Educational Designers embedded centrally and within 9 Faculties.